Nepal is annually affected by floods and landslides triggered by monsoon rains. So far the 2020 monsoon, particularly the landslides triggered by it, has been particularly deadly. This blog aims to explain the natural and anthropogenic causes of Nepal’s disaster risk and how this can be reduced.

What has been the impact of the 2020 monsoon in Nepal so far?

Floods and landslides are the most prominent and recurring hazards in Nepal, often resulting in disasters. Most of these rain-induced events occur during the monsoon season (June-September) when Nepal receives 80 percent of its total annual rainfall.

This year monsoon rains started on June 12th. Two days later the first landslides were triggered and 8 people lost their lives.

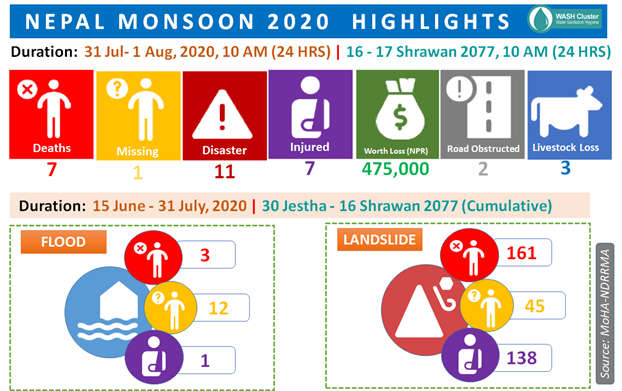

Floods and landslides have continued to affect several districts across Nepal as rainfall has been heavier than expected. The number of casualties and the loss of and damage to properties keeps increasing. According to National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority (NDRRMA) reports as of 31 July, 164 people have lost their lives due to landslides and floods, and many more are missing. The death toll this year is the worst in recent years, including the devastating floods in 2017 where 150 people lost their lives.

Different parts of Nepal are affected in different ways by the monsoon.

Landslides affect the hilly regions of Nepal…

Much of the mountainous terrain in Nepal lies on the tectonically active zone and has a fragile geological structure. Steepness of slopes and the swift flow of water bodies provide a geography susceptible to landslides triggered by the monsoon’s heavy rains. Changes in rainfall patterns, which has become severe and erratic, are contributing to extreme landslide events.

Growing populations, illegal settlements in hazard prone areas, and haphazard road constructions are also triggering landslides in hilly areas. The lack of proper land use planning means these hazards turn into disasters where lives and homes are lost.

…while the southern plains are battered by floods

In the plains of Nepal, including the Tarai district where Practical Action, as part of the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance, works with communities to build flood resilience, most settlements are located close to the river. Towns and cities tend to develop over time based on people’s mobility, proximity to India, and market opportunities, while risk factors (such as flooding) are often overlooked when building houses.

Encroachment of riverbanks, narrowing of streams, and changes to the course of rivers and streams have contributed to flooding. In the Churia region, illegal collection of sand, concrete, and boulders in hilly areas have increased the risk of both landslides and floods.

Disconnected institutions for Disaster Risk Reduction and Management

Disaster Risk Reduction and Management (DRR/M) institutions in Nepal are not as well connected as they should be, resulting in a weak DRR system. At a federal level, the NDRRMA has been established as per the Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Act of 2017 which clearly mandates it as the sole authority to prepare for and manage various disasters. The scope is wide ranging and the opportunities plentyful but the national authority is yet to establish connections, communications, and line management structures with provincial and local governments and disaster risk management committees.

Adding to the complexity is the fact that alongside the NDRRMA other national institutions also hold mandates for DRR/M related issues, not to mention that many agencies have devolved branches which in many cases have not yet been put in place, or are running effectively.

For a more detailed understanding of the Nepali federal governance structures and its challenges, and opportunities, for DRR/M you can read The governance of Nepal’s flood early warning system: opportunities under federalism from BRACED.

As focus remains on rescue and relief post disaster the hazards multiply

The Nepal government is yet to fully adopt and implement the idea of resilience building. Real progress is being made in the DRR field under the leadership of the government but when recovery still often fails to address the root causes of vulnerability threats and impacts increase, and the capacity of communities’ to withstand them decrease.

When a disaster affects any part of Nepal all levels of government scramble to deliver rescue work and relief distribution without sufficient coordination, despite the clear demarcation of responsibilities set out in the DRRM Act of 2017. Rescue and rehabilitation efforts are largely focused on easily accessible areas, ideally ones where the response will receive media attention, leaving many of those worst affected to fend for themselves.

How can we move forward from these challenges?

Preparedness must be a priority at all levels. Local governments should know where hazards exist; they should invest in research, and accordingly zone the landscape making it clear where it is safe for people to settle, for example using a traffic light system.

One important task to turn this around will be to ensure that all 753 Local Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Committees (LDMCs) across the country have the capacity and tools, including real time data for early warning, to save lives and livelihoods from disasters.

Early warning is key to early action

Community centred Early Warning Systems are an important aspect of ensuring that people have the knowledge to prepare for and respond appropriately to hazards. The technology, reach, and community trust in flood EWS has advanced in the past five years. The Department for Hydrology and Meteorology collects and analyses meteorological and hydrological data, and disseminates information on water discharge and weather forecasts as well as distributes early warnings via mass SMS to affected communities, through web alerts, and using social media.

To ensure that alerts reach all community members, including those without access to mobile phones or internet connection, Community Disaster Management Committees (CDMCs) play a part in disseminating early warning messages directly via sirens, speaker systems, megaphones, and different coloured flags. CDMCs are also active in training community members in how to responds to an early warning – how and where to evacuate for example. This link from the national to the very local is key to the success of flood EWS which save lives.

One of the main explanations for high death tolls from landslides compared to floods is that landslide EWS are not yet as advanced or reliable as their flood counterparts. More research is required to clearly understand the rainfall thresholds that trigger landslides before the learnings from successful, community centred flood EWS can be replicated to save more lives and livelihoods.

Before you go

If you work in the field of flood resilience in Nepal, and speak Nepali, our Nepal Flood Resilience Portal is home to a range of resources, news, and blogs that you might find useful.

Comments