The Porous City Network was established in 2017 to “increase urban resilience and adaptability to confront future climate uncertainty in vulnerable communities in Bangkok and other Southeast Asia Cities.” This ambitious project provides one example of how architectural solutions can empower citizens to increase their resilience to flooding.

Climate change in South East Asia

From 1990 to 2010, Southeast Asia was the fastest growing carbon emitter in the world, according to the Asia Development Bank. Although its historical share of global greenhouse gas emissions – primarily carbon dioxide, water vapor, methane, and nitrous oxide – is not as large, the region is on a trajectory that will make it a significant emitter in the future.

Nonetheless, the impacts of climate change in the region are already evident. One of the most impacted countries is Thailand. From 1997 to 2016, Thailand was ranked in the top 10 countries at long-term risk of climate change according to a 2018 report by Germanwatch – a non-profit think-tank in Bonn, Germany. According to Germanwatch, Thailand lost an average of 140 people and $7.6bn each year to climate events during this period.

One of the most damaging of these climate events in Thailand is flooding, and it is not the only country affected, as the US experienced late last year through Hurricane Harvey in Texas, where 88 people died.

How is climate change increasing floods?

The natural warming of the earth, that regulates our planet’s climate, occurs when energy from sunlight enters the earth’s atmosphere. Energy from this sunlight is absorbed by the earth, and some is reflected back as heat energy into the atmosphere. Of the heat energy reflected back, a portion is trapped in the atmosphere absorbed by greenhouse gases, warming the earth, and some escape among the gases back out into space.

A higher concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere increases the amount of heat trapped from the sun, as more of the reflected heat energy from the earth is absorbed by more greenhouse gases. The additional heating of the earth in this way is the main cause of global warming, and increasing floods.

93% of the extra heat trapped by manmade global warming pollution goes into the oceans, which make up 71% of the earth’s surface. The additional heat increases: the melting of the polar ice caps releasing more water into the oceans; the warming of oceans expanding the volume these vast bodies of water occupy; and the rates of water evaporation generating heavier and longer downpours of rain.

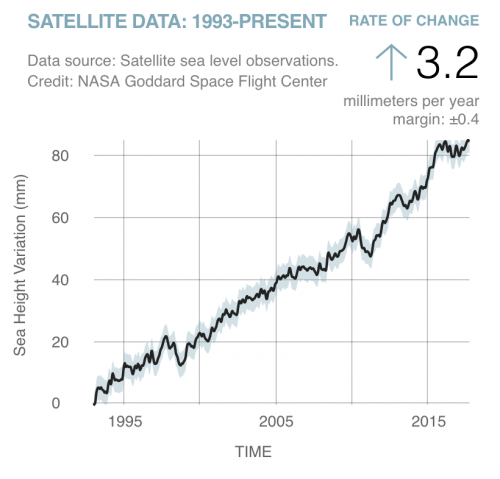

Since 1993 to 2017, global warming has contributed to an average sea level rise of 3.3 inches (84.8 mm), which is still rising at a rate of 0.13 inches (3.20 mm) every year, according to NASA.

Sea level rise and increased rain have posed serious flood risks for Bangkok, the capital city of Thailand, which is already close to sea level. To make things worse, rapid urban infrastructure developments and excessive pumping of groundwater have caused Bangkok to sink into its upper clay level. A lack of green space and drainage built into urban developments have meant that seasonal monsoon rains have no place to go, but to flood streets and houses. But, architecture may have an answer.

How can architecture help adapt to increasing floods?

Kotchakorn Voraakhom, a Harvard graduate and female landscape architect, experienced the problem of worsening floods as she grew up in Thailand. After completing her architecture graduate studies in the US in 2006, Voraakhom returned to Thailand wanting to offer up her skills to tackle this problem. However, whilst practicing landscape architecture in the public domain, Voraakhom “witnessed the development of many top-down public projects that should, but did not, lead the way towards a sustainable city,” she mentions.

Finding no local answer, Voraakhom founded Porous City Network (PCN) in 2017 aiming to “increase urban resilience and adaptability to confront future climate uncertainty in vulnerable communities in Bangkok and other Southeast Asia Cities,” Voraakhom continues. She works to do this by reclaiming urban porosity through a network of public green spaces.

Currently, PCN is working on a project with the Lat Phrao canal community, who live along the banks of one of Bangkok’s main drainage canals. When floods occur in the city, this community of over 4,000 households is worst hit. PCN is working with the government on a $76mn project to rebuild these homes and put up embankments on both sides of the canal to protect the communities, and city, from flooding.

Although these embankments are only a band-aid solution to flooding, PCN is using this project as an opportunity to improve the climate resiliency of these low-income houses, working together with the Community Organizations Development Institute (CODI) and the Bangkok Metropolitan Administration (BMA).

PCN entered the Lat Phrao community to listen to their needs, different to traditional infrastructure projects in Bangkok, and has integrated these needs into their architecture designs. Through a human-centered approach, Voraakhom has shown that working with the community to inform flood-resilient designs, running educational events and raising public awareness of environmental issues, the Lat Phrao community can be empowered with a voice, and live safely by the canal in the age of increasing floods.

So far Voraakhom’s work has been recognized with fellowships from Echoing Green, the Asia Foundation, and most recently TED. She has already been planning and working on projects beyond climate resilient housing – including rain gardens, green roofs, permeable parking, urban forests and farms – to address the root causes of increased flooding in her city.

So what?

Building flood-resilient housing alone will not be enough for Bangkok to adapt to increased flooding. However, with more sustainable development projects addressing the root causes of the flooding problem, and involving multiple layers of society – governments, corporations, non-profits and local communities – residents of Bangkok can be empowered to be part of the solution through architecture – and stop their beloved city from being forever submerged in the vast and growing ocean.

Comments