After years of political wrangling, we are finally seeing some progress in terms of wealthy nations shouldering some (small part) of the burden of Loss & Damage – but how do we make sure we don’t repeat the mistakes of the past? Debbie Hillier of Mercy Corps and Paul Knox Clarke of Adapt Initiatives explore how past humanitarian experience can provide some pointers to potential pitfalls and possibilities for Loss and Damage funding.

The issue of loss and damage – the harm caused by man-made climate change – has been on the UNFCCC agenda for many years; it has been pushed persistently by climate vulnerable nations, but until recently, they have been stonewalled. Developed countries were comfortable setting up technical working groups (through the Warsaw International Mechanism) but refused to engage meaningfully in issues around financing. That all changed at COP27. Finally states committed to establish new funding arrangements and a dedicated fund to address loss and damage. This was a huge breakthrough and the beginning of a vital process to address a critical gap in climate finance.

The COP decision set up a Transitional Committee to provide concrete proposals to establish loss and damage funding to be agreed at COP28 in Dubai. The committee is balanced across developed countries and developing countries, and is being asked to develop solutions for countries like Vanuatu, which is bearing the existential threat and devastating human costs of climate change. The second meeting of the Transitional Committee starts tomorrow (25th May), and has many difficult issues to negotiate and resolve.

Power play in relation to fund vs funding arrangements

There is a fine but critically important distinction between a fund, and funding arrangements. Until now wealthy nations have prioritised funding arrangements that they can control, such as the Global Shield and humanitarian aid. Developing countries are calling instead for a dedicated fund set up under the UNFCCC which could provide predictable funding based on need, rather than political headwinds.

There is a real issue of power here, which the humanitarian sector is very familiar with. International humanitarian funding is entirely discretionary (unlike, say, funding for UN peacekeeping, which is an obligatory assessed contribution under the UN Charter) and is provided according to the wishes of the donor. This means that:

- Funding sources are limited. In 2021, 59% of public contributions for humanitarian action were made by just three countries – USA, Germany and UK.

- Funding is unpredictable. Both the targeting of funding and overall amounts are subject to political preferences in donor countries, geopolitical dynamics, the global economy, and the ‘CNN effect.’

- Humanitarian donors retain a very high level of control over how funds are spent. There is no single global mechanism for prioritising need and allocating funding between different emergencies. Instead, donors mostly apply their own criteria, leading to disparities in funding from one disaster to another that are not necessarily related to the scale or intensity of needs. For example in 2021, 23% of UN coordinated appeals received more than three quarters of their funding requirements, while 13% received less than a quarter.

To avoid these pitfalls and ensure long term, predictable, well-targeted funding, a new loss and damage fund should be set up under the UNFCCC with a balanced governance structure in which contributing and recipient countries have equal voice and vote. This would build on the governance model of the Green Climate Fund, in order to bring greater transparency, accountability, and higher levels of country ownership than donor-driven funding arrangements.

Blind spot of fragility

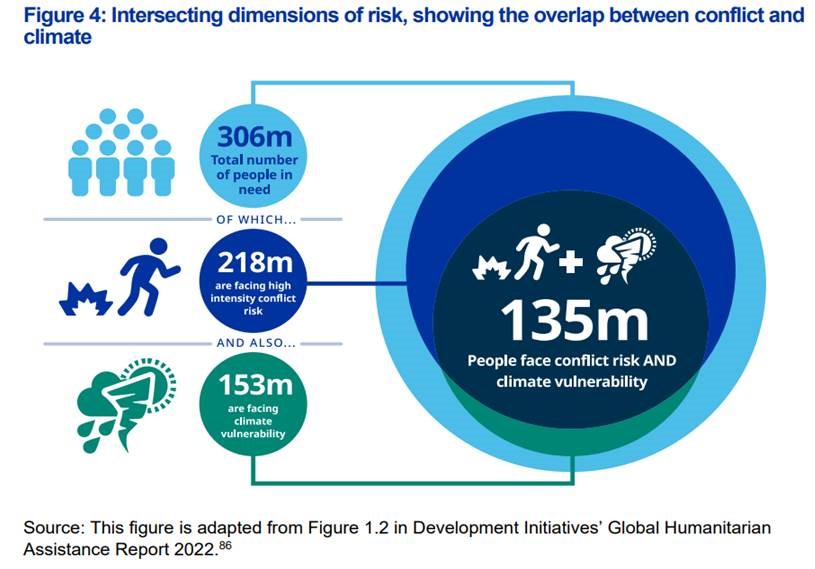

Another key issue is to consider how to deliver support to people in highly fragile or conflict–affected states (FCAS). They are often vulnerable to climate impacts as a result of decreased access to services and the difficulties of earning a living or building up reserves, even in the ‘good’ years, and their governments may be unwilling or unable or both to provide assistance. The figure below shows the huge overlap between people facing conflict and climate risk.

Despite this, the more fragile a country is, the less climate finance it receives: extremely fragile states averaged US$2.10 per person in adaptation financing compared to US$161.70 per person for not–fragile states. This is due to the need for elaborate programme designs and the low risk appetite (and in some cases demands for high returns) of finance. In sum, FCAS – and the affected communities within them – are effectively marginalised because they are ‘too difficult’ to support.

Humanitarians have much experience working in these contexts that could inform loss and damage funding, including around designing funding approaches that are tolerant of risk, open to a variety of actors beyond a single government ministry or body, and aware of the dangers of increasing conflict.

This is undoubtedly a complex issue, and one that has not been grappled with so far within the UNFCCC system, but will have to be considered in the loss and damage negotiations. The Transitional Committee may wish to institute a specific taskforce or workstream to consider this further.

Many other issues to resolve

As we stare down the barrel of 2023, there are many other issues to resolve before COP28, including the small matter of which countries should receive funding and which should pay. So far, we have seen skilful diplomacy from the Egyptian and UAE Presidencies, and Finnish and South African co-chairs, and generally positive engagement from TC members. Considering the technical and political complexity of the negotiations ahead, much much more of this will be required in the coming months.

Developed countries have already failed on their climate finance commitments. They continue to miss the target to provide $100bn a year for both mitigation and adaptation that could have helped avoid these losses. However difficult the work of the Transitional Committee, and however complex the political dynamics, the world’s wealthy nations cannot be seen to prevaricate now the journey to set up the new fund has begun.

For further evidenced lessons from the humanitarian sector, see a new working paper from the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance, authored by Paul Knox Clarke and Debbie Hillier, and informed by the experiences of humanitarian actors including Mercy Corps, the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the ADAPT initiative, among others.

This article was originally published by Duncan Green at From Poverty to Power. You can read the original here.

Comments