Version en espanol abajo.

The disasters that occurred in Peru and Ecuador after the presence of Cyclone Yaku and a recently confirmed El Niño phenomenon show the urgent need to understand the relationship between extreme events and climate change, opening the door to mechanisms of damage and loss.

The impact of Cyclone Yaku has been devastating. In Peru, heavy rains and floods have caused the death of more than 70 people and 15,000 victims, impacting 16 regions and 483 districts that have been declared in emergency. In Ecuador, where the cyclone passed previously, 5 deaths and at least 2 thousand families are affected. These tragic figures confront us with the question: why do these disasters occur?

Disasters are not natural

There is a clear relationship between disasters and vulnerability. For example, unplanned urbanization processes or the lack of social support mechanisms are factors that build vulnerability. Blaming nature contributes to crisis narratives that are often used to exonerate authorities from responsibility or promote reactive policies. We cannot ignore the structural factors that contribute to this vulnerability built by human actions. Rather, it is our responsibility to be critical of it.

“Vulnerability is a product of social and political processes that include elements of power and (bad) governance. These structural inequalities are often created deliberately and are anchored in social and political structures.” – Emmanuel Raju, Emily Boyd and Friederike Otto in Stop blaming the climate for disasters.

In this sense, there is a great responsibility in national and local governments to integrate disaster management as a cross-cutting element in all development processes. The current context has shown the limitations (and advances) that exist in consolidating corrective and prospective management strategies that reduce the already existing risk and prevent the formation of future risk.

However, it is necessary to recognize that our region is not alien to global dynamics and that the occurrence of these disasters responds to broader processes at the global level that also have corresponding responsibilities. Faced with this, the question arises: are these disasters the fault of climate change?

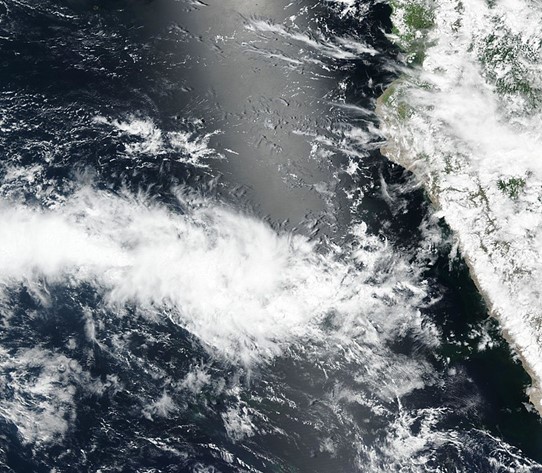

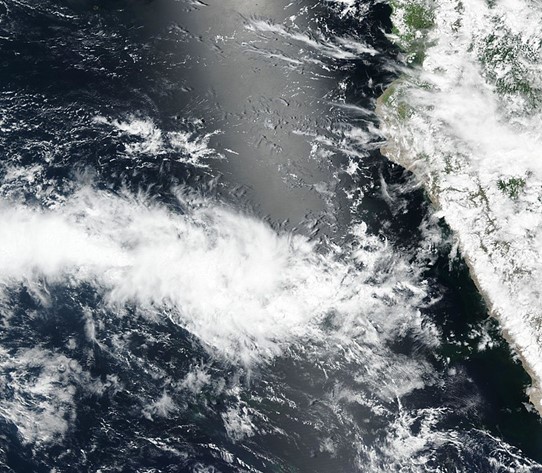

Did climate change cause Cylone Yaku?

The short answer is: we don’t know yet, but it is urgent to discuss it in order to find out.

Identifying the exact causes of an extreme weather event is difficult because various weather and climate processes interact.

What the scientific community has been arguing for some time now is that there is evidence to affirm that this type of event (heat waves, droughts, extreme rainfall, hurricanes, etc.) has been altered and is becoming more frequent or intense due to climate change caused by human influence.

However, that is not the whole story. There are important advances in the relatively new science of attribution that allows scientists to link specific aspects of extreme weather events to climate change on a case-by-case basis. The methodology for attribution was explained in the most recent report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): “This is done by estimating and comparing the probability or magnitude of the same type of event between the current climate – including increases in greenhouse gas concentrations and other human influences – and an alternative world in which atmospheric greenhouse gases remain at levels pre-industrial.” – Chapter 11, IPCC Sixth Assessment Report

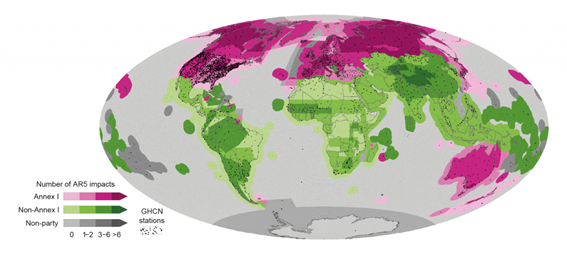

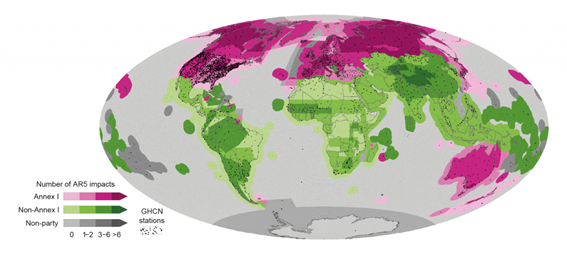

In other words, through climate models it is possible to quantify the influence that climate change has had on specific extreme events. For example, specialists from the World Weather Attribution initiative studied the floods that occurred between May and June 2022 in northeastern Brazil and determined that the rainfall that caused them was increased by climate change. However, the areas with the greatest impacts on climate change are also the areas for which there is less official data. We urgently need to generate climate information.

In this sense, from Practical Action, through the Flood Resilience and Anticipatory Action Program in the Andes, we seek to contribute to expanding the scope of rainfall monitoring and bring people and communities closer to this information with initiatives that combine the use of free technologies and citizen science.

Attribution is the first step towards climate justice

Let’s think again about responsibility in the face of disasters. If it is possible to affirm that an extreme event is attributable to climate change, who would be responsible for it then?

In 2017, Saúl Luciano Lliuya, a farmer from the Peruvian Andes, filed a lawsuit against the German company RWE for its contribution to the melting of glaciers that caused the water level of the Palcacocha lagoon to rise, increasing the risk of floods and droughts for his crops and those of his community. This lawsuit seeks to set a global precedent and refers to an attribution study. This has been reviewed by German judges and experts who have visited the affected area in Huaraz. The case of Saúl Luciano Lliuya is an emblematic example of how climate attribution opens the door to loss and damage mechanisms.

Loss and damage goes beyond the limits of climate adaptation and seeks to address the enormous debt owed by the largest emitters in the global north to the most vulnerable nations that have contributed the least to global warming and yet suffer its most severe impacts. Climate change losses in developing countries are estimated to be between $290 billion and $580 billion by 2030.

It is not for nothing that one of the most controversial and relevant points of the last United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP27) was the agreement to create a loss and damage fund for vulnerable countries financed by those who have contributed the most to global warming. Although the agreement does not yet spell out specific legal responsibility, it has been recognized as a step forward toward climate justice.

These key negotiations around loss and damage mechanisms were led by the delegation of Pakistan, a country that faced the onslaught of a climate catastrophe in 2022. Massive floods that year impacted 33 million people and left a third of the country literally underwater, with Pakistan responsible for less than 1% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

“It may be too late for the victims of Pakistan’s floods, but it is my fervent hope that the loss and damage mechanism will be ready to help the next devastated country. Because what happened to Pakistan will not stay in Pakistan. In 2022 it was my country; Next year could be anywhere. Or all over the world. The future of the planet depends on our joint efforts, which must move forward now.” – Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, Foreign Minister of Pakistan.

The expectation about loss and damage mechanisms is high, but there is also a lot of concern about unfulfilled commitments. We cannot forget that in 2009 developed countries pledged to mobilise USD 100 billion annually through the Green Climate Fund. This goal has not been met at present.

Beyond climate adaptation

The presence of Cyclone Yaku confronts us with a complex reality regarding disaster risk management in the region: our actions and strategies have so far been insufficient.

The crisis we are facing due to this climate event forces us to think beyond adaptation and mitigation and incorporate models that aim at reparation for the benefit of the communities most vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

It is also urgent to optimize humanitarian response actions with new mechanisms, such as the anticipatory action approach that aims to act in the window of time between the issuance of an alert and before the impact of the crisis is felt.

This, of course, implies recognizing, continuing and strengthening the prevention actions that have worked and have contributed to dealing with this emergency. We must continue to bet on scaling up community-centered early warning systems and strengthening community response brigades who are the front line in every emergency situation.

There is a long road ahead to determine whether the onslaught of Cyclone Yaku can be attributed to climate change. However, we are certain that the frequency and intensity of this type of event will continue to grow and action is needed.

Ciclón Yaku y el cambio climático

Los desastres ocurridos en Perú y Ecuador tras la presencia del ciclón Yaku y un recientemente confirmado fenómeno de El Niño evidencian la urgente necesidad de entender la relación entre eventos extremos y el cambio climático abriendo la puerta a mecanismos de daños y pérdidas.

El impacto del ciclón Yaku ha sido devastador. En Perú, las lluvias intensas y las inundaciones han causado la muerte de más de 70 personas y 15 mil damnificados, impactando a 16 regiones y 483 distritos que han sido declarados en emergencia. En Ecuador, donde el ciclón pasó previamente, se calculan 5 fallecidos y al menos 2 mil familias damnificadas. Estas trágicas cifras nos confrontan con la pregunta: ¿por qué ocurren estos desastres?

Los desastres no son naturales

Existe una clara relación entre desastres y vulnerabilidad. Por ejemplo, procesos de urbanización no planificados o la falta de mecanismos de apoyo social son factores que construyen vulnerabilidad. Culpar a la naturaleza contribuye a narrativas de crisis frecuentemente aprovechadas para exonerar de responsabilidades a autoridades o impulsar políticas reactivas. No podemos desconocer los factores estructurales que contribuyen a esta vulnerabilidad construida por acciones humanas. Más bien, es nuestra responsabilidad ser críticos de ello.

“La vulnerabilidad es producto de procesos sociales y políticos que incluyen elementos de poder y (mala) gobernanza. Estas desigualdades estructurales se crean de forma a menudo deliberada y están ancladas en las estructuras sociales y políticas.” – Emmanuel Raju, Emily Boyd y Friederike Otto en Stop blaming the climate for disasters

En este sentido, existe una gran responsabilidad en gobiernos nacionales y locales para integrar la gestión de desastres como un elemento transversal a todos los procesos de desarrollo. El contexto actual ha evidenciado las limitaciones (y avances) que se tienen para consolidar estrategias de gestión correctiva y prospectiva que disminuyan el riesgo ya existente y prevengan la conformación de riesgo futuro.

Sin embargo, es necesario reconocer que nuestra región no es ajena a dinámicas globales y que la ocurrencia de estos desastres responde a procesos más amplios a nivel mundial que también tienen responsables correspondientes. Frente a ello surge la pregunta: ¿estos desastres son culpa del cambio climático?

¿El cambio climático ocasionó al ciclón Yaku?

La respuesta corta es: aún no lo sabemos, pero es urgente discutirlo para poder averiguarlo. Identificar las causas exactas de un evento climático extremo es difícil pues interactúan diversos procesos meteorológicos y climáticos.

Lo que la comunidad científica sostiene desde hace un tiempo es que existe evidencia para afirmar que este tipo de eventos (olas de calor, sequías, lluvias extremas, huracanes, etc.) han sido alterados y están siendo más frecuentes o intensos debido al cambio climático provocado por la influencia humana.

Sin embargo, esa no es toda la historia. Existen avances importantes en la relativamente nueva ciencia de la atribución que permite a los científicos vincular aspectos específicos de eventos meteorológicos extremos al cambio climático analizando caso por caso. La metodología para la atribución fue explicada en el más reciente informe del Grupo Intergubernamental de Expertos sobre el Cambio Climático (IPCC): “Esto se hace estimando y comparando la probabilidad o magnitud del mismo tipo de evento entre el clima actual -incluidos los aumentos de las concentraciones de gases de efecto invernadero y otras influencias humanas- y un mundo alternativo en el que los gases de efecto invernadero atmosféricos se mantuvieran en niveles preindustriales.” – Capítulo 11, Sexto Informe de Evaluación del IPCC

Es decir, mediante modelos climáticos es posible cuantificar la influencia que ha tenido el cambio climático en eventos extremos específicos. Por ejemplo, especialistas de la iniciativa World Weather Attribution estudiaron las inundaciones ocurridas entre mayo y junio de 2022 en el noreste de Brasil y determinaron que las lluvias que las ocasionaron fueron incrementadas por el cambio climático.

Sin embargo, las zonas con mayores impactos frente al cambio climático son también las zonas de las que menos datos oficiales se tienen. Necesitamos urgentemente generar información climática.

En este sentido, desde Practical Action, a través del Programa de Resiliencia ante Inundaciones y Acción Anticipatoria en los Andes, buscamos contribuir a ampliar el alcance del monitoreo de precipitaciones y acercar a las personas y comunidades a esta información con iniciativas que combinan el uso de tecnologías libres y la ciencia ciudadana.

La atribución es el primer paso hacia la justicia climática

Volvamos a pensar en la responsabilidad frente a los desastres. De lograrse afirmar que un evento extremo es atribuible al cambio climático ¿quién sería responsable de ello entonces?

En 2017, Saúl Luciano Lliuya, un campesino de los Andes peruanos, planteó una demanda a la empresa alemana RWE por su contribución al deshielo de glaciares que ocasionaron el aumento del nivel del agua de la laguna Palcacocha incrementando el riesgo de sus cultivos y los de su comunidad a inundaciones y sequías. Esta demanda busca sentar un precedente global y hace referencia a un estudio de atribución. Este ha sido revisado por jueces y expertos alemanes que han visitado la zona afectada en Huaraz. El caso de Saúl Luciano Lliuya es un ejemplo emblemático de cómo la atribución climática abre la puerta a los mecanismos de pérdidas y daños.

Las pérdidas y daños van más allá de los límites de la adaptación climática y buscan abordar la enorme deuda que tienen los más grandes emisores del norte global hacia las naciones más vulnerables quienes menos han contribuido al calentamiento global y, sin embargo, sufren sus impactos más severos. Se calcula que las pérdidas por el cambio climático en los países en desarrollo estarían entre los 290 000 millones y 580 000 millones de dólares al 2030.

No es por nada que uno de los puntos más controversiales y relevantes de la última Conferencia de las Naciones Unidas sobre el Cambio Climático (COP27) fue el acuerdo para crear un fondo de pérdidas y daños para países vulnerables financiado por quienes más han contribuido al calentamiento global. Aunque el acuerdo aún no explicita la responsabilidad legal específica, ha sido reconocido como un paso adelante hacia la justicia climática.

Estas negociaciones clave en torno a los mecanismos de daños y pérdidas fueron lideradas por la delegación de Pakistán, un país que enfrentó los embates de una catástrofe climática en 2022. Las enormes inundaciones de ese año impactaron a 33 millones de personas y dejaron a un tercio del país literalmente bajo el agua, siendo Pakistán responsable de menos del 1% de las emisiones globales de gases efecto invernadero.

“Puede que sea demasiado tarde para las víctimas de las inundaciones de Pakistán, pero tengo la ferviente esperanza de que el mecanismo de pérdidas y daños estará listo para ayudar al próximo país devastado. Porque lo que le ocurrió a Pakistán no se quedará en Pakistán. En 2022 fue mi país; el año que viene podría ser cualquier lugar. O en todo el mundo. El futuro del planeta depende de nuestros esfuerzos conjuntos, que deben avanzar ahora.” – Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, Ministro del Exterior de Pakistán.

La expectativa sobre los mecanismos de pérdidas y daños es grande, pero también existe mucha preocupación sobre los compromisos no cumplidos. No podemos olvidar que en 2009 los países desarrollados se comprometieron a movilizar 100 000 millones de dólares anuales mediante el Fondo Verde para el clima. Esta meta no ha sido cumplida en la actualidad.

Más allá de la adaptación climática

La presencia del ciclón Yaku nos confronta a una realidad compleja sobre la gestión del riesgo de desastres en la región: nuestras acciones y estrategias al momento han sido insuficientes.

La crisis a la que nos enfrentamos por este evento climático nos obliga a pensar más allá de la adaptación y la mitigación e incorporar modelos que apunten a la reparación en beneficio de las comunidades más vulnerables a los efectos del cambio climático.

Asimismo, es urgente optimizar las acciones de respuesta humanitaria con nuevos mecanismos como, por ejemplo, el enfoque de acción anticipatoria que apunta a actuar en la ventana de tiempo que existe entre que se emite una alerta y antes que se sienta el impacto de la crisis.

Esto, por supuesto, implica reconocer, continuar y fortalecer las acciones de prevención que sí han funcionado y han contribuido a hacer frente a esta emergencia. Debemos seguir apostando por escalar los sistemas de alerta temprana centrados en las comunidades y el fortalecimiento de las brigadas de respuesta comunitaria quienes son la primera línea en cada situación de emergencia.

Existe un largo camino por delante para determinar si los embates del ciclón Yaku pueden atribuirse al cambio climático. Sin embargo, tenemos la certeza de que la frecuencia e intensidad de este tipo de eventos seguirá creciendo y es necesario tomar acción.

Comments