Communities affected by both extreme weather and conflict are being neglected by donors and international climate funds – but new evidence from the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance and Mercy Corps shows that solutions are available.

Where the climate crisis endangers lives and livelihoods – often of those who have contributed the least to global carbon emissions – resources are urgently needed to adapt to the changing conditions and ensure long-term safety and prosperity.

However, fragile and conflict-affected countries are being left behind, with donors and international climate funds instead prioritizing relatively stable countries for adaptation funding. In many cases, this means neglecting communities where the need for climate adaptation is greatest; 18 of the top 25 countries currently most vulnerable to climate change are classified as fragile or conflict-affected.

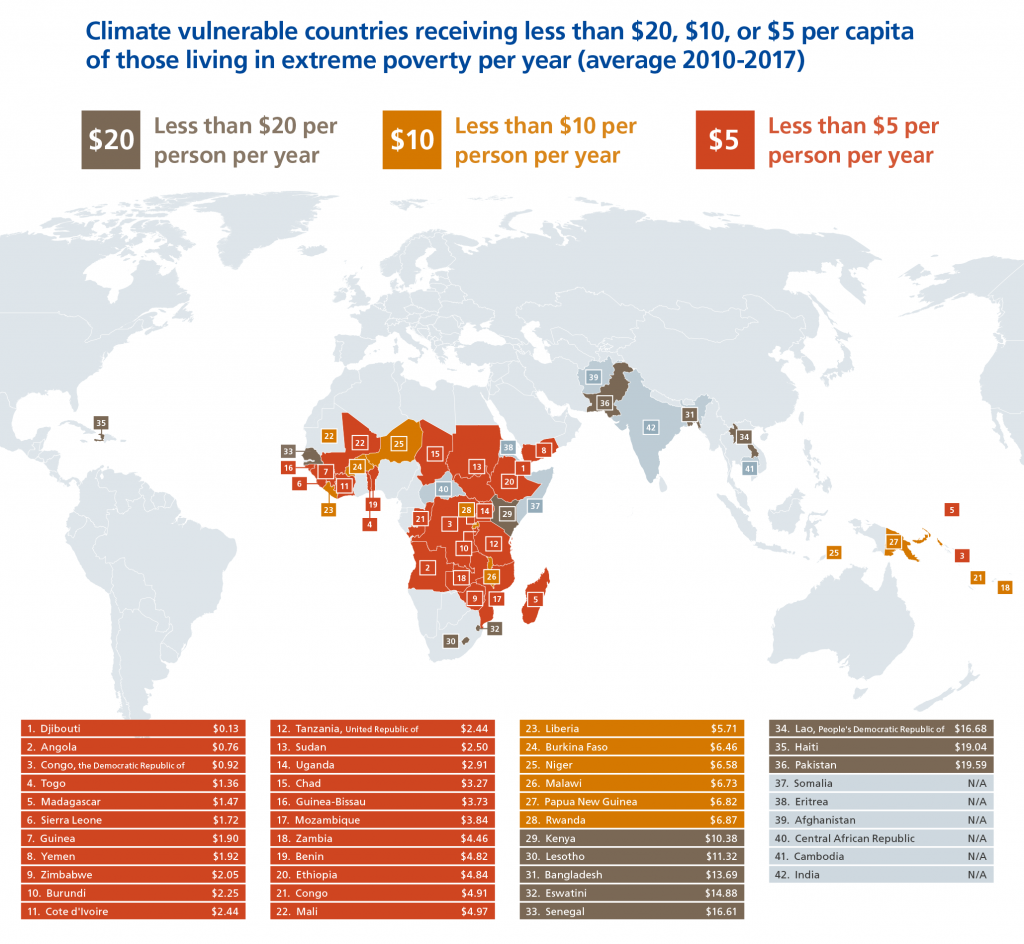

Alarmingly, the more fragile a country is, the less climate finance it has received from bilateral funders and multilateral climate funds. Between 2010 and 2017, extremely fragile states received an average of $2.1 per person per year in adaptation financing, compared to $161.7 per person for non-fragile states. Looking at specific countries reveals major shortfalls: Niger received only $6.58 per person per year, Mali received $4.97, Zimbabwe received $2.05, and Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) only received $0.92.

However, as new research from the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance shows, solutions to improve climate financing equity can be found outside of the climate space. By heeding the lessons of the UN Secretary-General’s Peacebuilding Fund, the COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access (COVAX) programme and others, climate funders can ensure fragile states are included in the distribution of urgently needed adaptation funding.

In short, it is simply not true to claim that delivering climate adaptation work in fragile contexts cannot be done.

Why fragile states are overlooked on climate finance

For conflict-affected countries, barriers to accessing climate finance exist at every stage of the process. In many cases, a donor will be discouraged from engaging in fragile contexts due to their complex nature, especially when conflict dynamics evolve rapidly, and security can deteriorate quickly. Weak government institutions may also prevent nations from meeting stringent requirements designed to reduce the risk of fraud and corruption.

Current international climate finance architecture also prioritizes large-scale adaptation projects – such as flood prevention and ecosystem rehabilitation – that contribute to national development plans and deliver financial returns on investment.

Where climate funders display inflexible operational bureaucracy, programmes are likely to fail in fragile states as they find it difficult to adapt to inevitable changing conditions. Monitoring and evaluation practices are also often unsuitable, lacking the longer timeframes to evaluate integrated climate–conflict programming effectively.

The climate funders’ tendency to fund short-term projects in fragile states is also a challenge, since countries won’t be able to achieve adaptation outcomes without long-term financing.

Finding a path forward on climate finance

While there are indeed many obstacles to providing climate finance to fragile states, none is insurmountable. Indeed, there is plenty of evidence that shows how ambitious projects are possible in highly complex contexts. For example, look at the impact of the Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) – the UN’s financial instrument of first resort to sustain peace in situations at risk of or affected by, violent conflict.

The PBF was established to drive more effective, strategic and cohesive action by the UN in the crucial gap between the winding down of emergency humanitarian funding, and the materialization of development funding. Risk is tolerated in PBF projects because it is well understood, assessed and anticipated. With this solid grasp of the realities on the ground, the PBF is willing to be innovative and catalytic in what it funds.

The PBF also sets asides budget in its programmes to support national, local and grassroots organizations, which recognizes the critical role that civil society actors play in areas of contested control. Furthermore, flexibility is written into guidelines and operational protocols to ensure that projects can adapt to fluid contexts. Among the PBF’s successes is the reduction of tensions between farmers and herders in West Africa and the Sahel, achieved by identifying acceptable routes for livestock migration that are likely to reduce the chance of conflict.

Further lessons can also be gleaned from the work of COVAX, which had to navigate vaccine supply and distribution in fragile and conflict-affected states. Simplified delivery structures sped up the administrative processes in the target countries, meaning that significant logistical and funding gaps in the Central African Republic, Somalia and elsewhere were quickly identified and addressed.

The emerging financial instrument of Peace Bonds also holds the potential to deliver lasting change, as do ring-fenced contingent funds for responding to shocks, known as Crisis Modifiers. Mercy Corps has incorporated these into our work in Ethiopia, to ensure that climate adaptation gains aren’t eroded by hazards like droughts and floods. It’s one of many ways in which climate adaptation programmes can be tailored to achieve meaningful results, even in the face of considerable challenges.

Act now to prevent future crises

The issue isn’t going away; by 2030, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates that 2.2 billion people – 26% of the world’s population – will live in fragile states. Meanwhile, the climate crisis is amplifying existing environmental, social, political and economic challenges in fragile states – and a failure to sufficiently fund adaptation efforts will only make things worse.

International organizations and climate funders must be prepared to embrace fresh approaches to meet the scale of the challenge.

This article was originally published by the World Economic Forum on 14th February. You can read the original here.

Comments