The New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) is a global climate finance target set to be agreed in November 2024 at COP29. It is a replacement for the current goal, established at COP15 in 2009, where developed countries pledged to collectively mobilize $100 billion per year to support climate action in developing countries.

While this proved that a collective goal on climate finance was possible, the target figure has been consistently missed. Much of the reason for this comes down to flaws at the heart of the process, including the prioritization of political compromise over actual needs, and the absence of detail on how much each country could – and should – contribute.

At COP21 in 2015 in Paris, Parties decided they ‘shall set a new collective quantified goal from a floor of $100 billion per year, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries.’ The process began at COP25 in 2019, and will culminate later this year in Baku, Azerbaijan.

Video: Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance colleagues from Jordan, Malawi, Montenegro and Bangladesh break down the NCQG. View all videos here.

The Zurich Climate Resilience Alliance works in many countries that have been significantly impacted by the climate crisis. In 2023, Cyclone Freddy wreaked havoc in Malawi, claiming over 1,000 lives and displacing hundreds of thousands more; deadly flash floods are a regular occurrence in Jordan; and the livelihoods of coastal communities are under threat in Indonesia.

"The adoption of an ambitious new goal at COP29 is essential to support climate-vulnerable communities"

What is already a grave situation for many is expected to get even worse in the future. The world continues to heat up at an alarming rate, while storms intensify and growing seasons shift and shorten. The adoption of an ambitious new goal at COP29 is therefore essential to support climate-vulnerable communities.

Clearly, the current provision of $100 billion per year is not near enough to address current and future needs, but debate around the figure that should feature in the new goal (known as the 'quantum') continues; different estimates put the needs of developing countries at between $2.4 trillion and $5.9 trillion per year by 2030. In any case, the figure is certainly expected to be in the trillions rather than the billions.

This means that the NCQG must display a level of ambition not previously witnessed. Such a massive scale-up of climate finance from its current state will be difficult to achieve, especially at a time when aid budgets are under pressure and ‘new and additional funding’ for climate finance is rarely forthcoming. That said, the NCQG represents the first opportunity in fifteen years to undergo the kind of major course-correction on climate finance that will be required to meet the needs of developing countries.

Below: Women in Madani village, Malawi doing laundry with the residual water from the flood caused by Cyclone Freddy. Photo: Concern Worldwide

A woman pushes her bike through the flooded streets of her village on the northern coast of Central Java, Indonesia. Photo: Mercy Corps

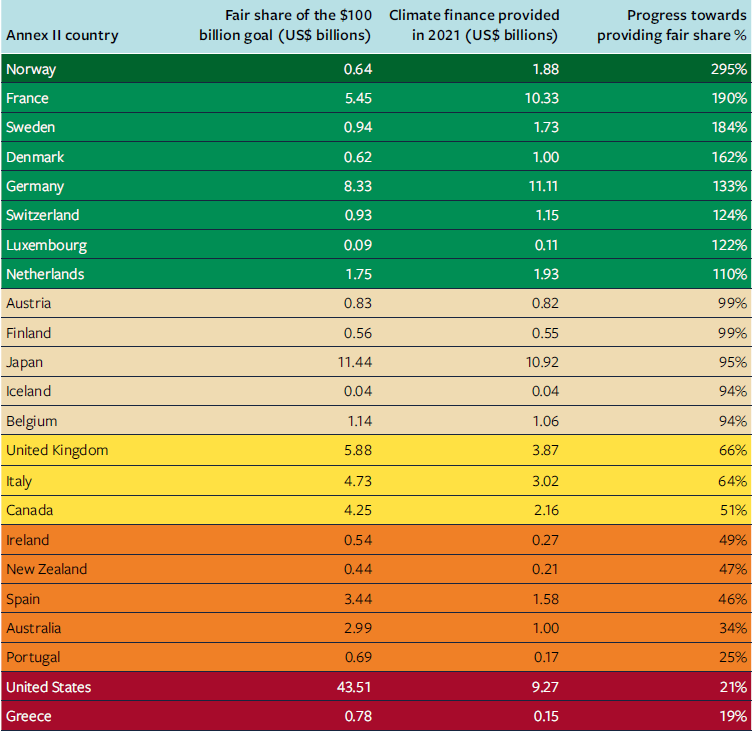

Image: Scorecard of progress towards Annex II countries’ fair share of the US$100 billion climate finance goal. Source: ODI/Zurich Climate Resilience Alliance

The question of which countries should provide climate finance has been a long-standing point of contention – and as conversations around the NCQG progress, it is only becoming more so.

Climate change is everyone’s problem, and therefore all countries have a shared responsibility to address it. While this was acknowledged at the founding of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in 1992, it was also recognized that the developed countries historically responsible for causing climate change – which are largely those with the most ability to pay – should contribute the most climate finance.

"Developed countries have clear, unequivocal and legally-binding obligations to deliver climate finance"

This principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’ (CBDR-RC) appears frequently in UNFCCC agreements, most significantly in the Paris Agreement of 2015 – article 9 of which states that “Developed country Parties shall provide financial resources to assist developing country Parties with respect to both mitigation and adaptation.”

In this agreement and others, developed countries have clear, unequivocal and legally-binding obligations to deliver climate finance – yet in practice there has been little attempt by developed countries to contribute as much as they should. In partnership with ODI, the Zurich Climate Resilience Alliance has spent the last few years tracking countries’ contributions, and comparing it to their ‘fair share’ of the $100bn target based on each nation’s historical responsibility for cumulative greenhouse gas emissions, gross national income and population size. This revealed that most countries are not paying their fair share, leaving a huge gap in global climate finances.

As negotiations continue, it is vital that tangible, equitable and binding targets for each contributor are identified, and intrinsically linked to historical responsibilities and ability to pay – supplemented by continued voluntary contributions from some developing countries. Anything less will leave the NCQG likely to fall short in the same ways that its predecessor did, with catastrophic implications for climate-vulnerable communities.

Another improvement that the NCQG can make to the $100bn target is the establishment of agreed sub-goals for mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage. As our research with ODI revealed, the current situation has led to a major imbalance between mitigation and adaptation, resulting in an increasing adaptation gap.

Establishing separate goals for these very different areas of action – based on global levels of need for each, with regular reviews and adjustments – should result in a more equitable and balanced distribution, and ensure adaptation finance does not get lost or eclipsed by support for mitigation efforts. It will also ensure that finance is not taken from one to fulfil commitments to the other.

The existing target of $100bn a year also calls for this to be “mobilized” by developed countries – which can include making funds available through incentives, innovative finance approaches, and changes to policy – and not just provided by them. This includes private climate finance which, while welcome in some cases, is ill-suited to others. Most private sector finance goes towards projects in middle-income countries with relatively low risk profiles – and of that, only a small fraction funds adaptation projects, where the returns are less obvious. Meanwhile funding for loss and damage is only ever likely to come from the public sector.

Public finance provision must therefore serve as the basis for the NCQG, with no combined target for both public and private sources of finance. Instead, a separate, secondary target for the mobilization of private finance should be established.

Funding recovery from climate shocks: what will you decide? Play our interactive video

To further align with the principle of CBDR-RC, public climate finance must prioritize grants (which need not be repaid) over loans, to avoid saddling crisis-stricken developing countries with an unjust debt burden. The Jubilee Debt Campaign calculates that, on average, low-income countries now spend five times more on debt repayments than on tackling climate change. As extreme weather events increase in frequency, this can mean that communities rocked by storms and floods may still be recovering from a previous one (as was the case with Cyclone Freddy).

Spiralling debt crises can be avoided if the NCQG can improve the quality of finance as well as the quantity. Delivering most adaptation and loss and damage finance through grants, as well as ensuring that any loans are highly concessional and flexible, is the best option.

Deciding who pays, and how much, will provide some much-needed clarity on what funds will be available – as will the proposed sub-goals for mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage. However, that’s only one side of the equation; for the NCQG to be successful, it must also improve access to climate finance so that funds can swiftly reach those most in need.

Between bilateral donors, multilateral development banks (such as the World Bank) and multilateral climate funds (such as the Green Climate Fund), the current landscape of climate finance is incredibly fragmented. Access to finance varies in myriad ways depending on the provider, but almost all use slow and complex processes that are often poorly suited to vulnerable countries’ needs. For example, the IIED determined that it takes on average over 1,100 days to gain access to the Green Climate Fund’s resources.

The NCQG can improve the situation by encouraging funders to prioritize direct access to climate finance for developing countries. A portion of the funds could also be ring-fenced for the Least Developed Countries (LCDs), whose levels of fragility often severely impede their access to climate finance.

"Climate disasters tend to have a disproportionate impact on women and girls"

Something else frequently overlooked in climate finance discussions is the fact that it should be gender-responsive, but often isn’t. In 2021, out of a total of $28.2 billion in adaptation funding provided by developed countries, less than half was reported to include gender equality as an objective.

Given that climate disasters tend to have a disproportionate impact on women and girls, the NCQG must offer solutions or risk exacerbating gender inequalities further still. Encouraging greater transparency through comprehensive use of the OECD’s gender markers, hand in hand with the establishment of targets for the share of climate finance that should address gender equality, will go a long way to addressing persistent injustices.

Below: Red Cross Volunteers in Chingwizi, Zimbabwe, construct shelters for flood-displaced families. Between 2010 and 2017 - like many similarly fragile and conflict-afflicted states - the country received less than $5 of climate finance per person, per year. Photo: Hansika Bhagani, IFRC

Two women in Dhangadi, Nepal who have participated in the Alliance's efforts to strengthen community resilience to frequent heavy rains and unprecedented flooding. Photo: Alexandra Bingham, Mercy Corps

An agreement on the NCQG is expected at COP29 in Azerbaijan, with some key milestones between now and November – including various meetings of technical experts, a ministerial dialogue expected in September, and the publication of the NCQG co-chairs’ annual report (set to include ‘a substantive framework for a draft negotiating text’) by mid-October. More details are available on the UNFCCC website.

Navigating the process to reach a positive outcome at COP29 will not be easy, and there are myriad obstacles that have the potential to weaken the agreement. Developed countries must be reminded of their obligations, and of the consequences of failure; prevailing myths – that private finance holds the answer, that accountability is undeliverable, and that developed countries simply do not have the means to provide new and additional climate finance, to name just a few – must be challenged and debunked; and public perception of the scale of the challenge, and the level of action required to meet it, must undergo a radical shift.

Regardless, the evidence is overwhelming: for those affected by climate change today, and those who will be impacted in the future, world leaders must not let COP29 pass without delivering an ambitious NCQG that can begin to turn the corner on addressing the climate crisis.

This article will be updated as negotiations continue.Please check back for the latest on the NCQG, and follow the Zurich Climate Resilience Alliance on X and LinkedIn.